When I wrote about Hunter S Thompson last week, I didn’t know that it was the anniversary of his death two days later. The excitement this coincidence provoked in me lasted for a day or so, reminding me of the early inspiration I felt writing about autism, when I would half-joke to myself that the masses of undiagnosed dead autistic people were speaking through me.

Sometimes what I write about on a Saturday is something that’s been brewing throughout the week, and sometimes Saturday comes and nothing has been brewing so I draw on the well of notes I made last year when I was deeply focused on autism. Without anything brewing last week, for a few days, without considering who or what to write about, I felt automatically pulled to sketch Hunter S Thompson, one of the people I already had material on. Then a few days after publishing I noticed he’s trending on twitter.

In the past I might have examined this coincidence with the aim of explaining it away, but now I revelled in the exciting joy and mystery of it, which has an important motivating effect, imparting the sense that what I do is meaningful independent of its reception or rewards, the coincidence itself being validation enough. As I have mentioned before there is a theme among some autistic people of being attuned to the weird and eerie, and of seeking explanations for what or why that is.

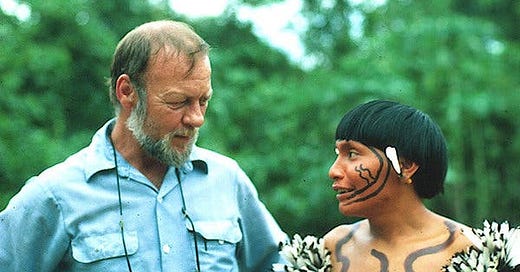

Last week I watched the documentary Secrets of the Tribe that in retrospect relates to this theme. The film documents the controversy surrounding anthropologists studying the Yanomami people of the Amazon, considered one of the cultures least influenced by modern civilization, thus valuable for insights into early human hunter-gatherer life. The controversy boils down to nature vs nurture or biology vs culture, and its ad-hominem reflections in the conduct of the fieldworkers, where one side is accused of colonialist genocide and the other of romanticism and paedophilia.

The film is restrained and even-handed, making the controversy and feuding in this academic discipline its main subject rathe than trying to adjudicate between the feuding parties. It reminded me of Janet Malcolm’s books about similar controversy and feuding in obscure disciplines, such as psychoanalysis (In the Freud Archives) or literary biography (The Silent Woman). As in these books, the film documents professionals questioning (or slandering) the methods, motives and interpretations of each other’s work, and considers the personalities and relationships of influential knowledge producers.

Besides the possibility of autism in these feuding anthropologists - who go off into the jungle alone to live with, observe and note down all the tiny details and patterns of an unfamiliar society, decoding and learning from scratch a language no westerner has ever learned before - they are sort of asking the questions that all verbal autistic people may have asked themselves at some point before their diagnosis: Why do I think, speak, behave, sense and feel the way I do? how hardwired is it? how much a product of my upbringing and society is it?

To accept the autism diagnosis is to accept it’s a particular type of hardwiring. This has refreshed and empowered my ability to interpret the patterns and coincidences I see as I will.